This deserves critical reflection, though not because it redeems Refugia (spoiler: it doesn’t). Second, a key point about Cohen and Van Hear’s project that those earlier critiques did notaddress is its use of fiction as a means of rethinking refugee protection-that is, its literary imagination. First, at some risk of flogging a dead horse, the book-length problems merit an essay-length critique, lest any of those policymakers, practitioners, or activists be tempted to lend Refugia more credence than it warrants. But it’s worth returning to this longer version of the argument, for two reasons.

Quite the opposite: it builds the dream palace of technical fixes to even loftier heights, while the gaps in its foundations yawn ever wider. None of these issues is resolved in the book-length version of the argument.

#Making a dystopia in venture towns how to

Lutz noted that the plan ignored differences between refugees (who may include perpetrators as well as victims of persecution), said nothing about how Refugia’s people would reach agreement on how to achieve a ‘just’ society, and left unanswered the question of the economic system it would adopt. Barbelet and Bennett observed that the idea ‘imagines a solution where refugees survive but do not thrive’, proposing a technical fix that does not address refugees’ structural economic, legal, and social precarity. An earlier version was the subject of a round table in the inaugural issue of Migration & Society: Advances in Research, where Van Hear presented the idea in outline, with critical responses from Véronique Barbelet and Christine Bennett at the Humanitarian Policy Group and Helma Lutz of Goethe University Frankfurt (Van Hear et al. The project was familiar to researchers and practitioners in the field long before the book came out: the authors presented their ideas widely, in person and in writing.

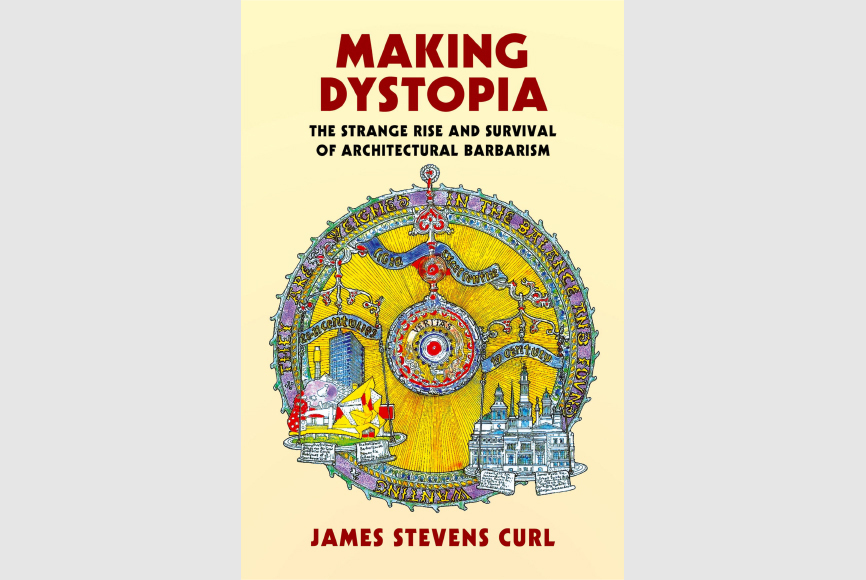

This is not so much a proposal to reform or replace the current refugee regime as an effort to imagine a better world that, they hope, might be within our reach-in as little as a decade, if only refugees will grasp it for us. How can this situation be resolved? Cohen and Van Hear engage in utopian thinking to produce a ‘social science fiction’ in which a transnational global polity of refugees, wrought by the efforts of refugees themselves, emerges. Like these other books, Refugia starts with the now standard claim that record numbers of people are being displaced, of whom a shrinking proportion can hope to find a ‘durable solution’ while an overstretched refugee system keeps the rest in humanitarian limbo. Alexander Aleinikoff and Leah Zamore’s The Arc of Protection: punchy little books of about 150 pages, designed to be read and digested quickly by policymakers, humanitarian practitioners, and activists. Robin Cohen and Nick Van Hear’s Refugia falls somewhere in the middle, like T. The past few years have seen a flurry of proposals to reform the international refugee regime, ranging in scale and complexity from a tweet-Egyptian telecoms billionaire Naguib Sawiris’s offer to buy a Mediterranean island from Greece or Italy and put refugees there-to full-length books like Alexander Betts and Paul Collier’s Refuge,which proposed to dismantle the entire rights-based regime built around the 1951 refugee convention (White 2019). Refugia: Radical Solutions to Mass Displacement. Front cover of Cohen and Van Hear, Refugia.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)